ARTICLES & INTERVIEWS

Feb 2, 2019

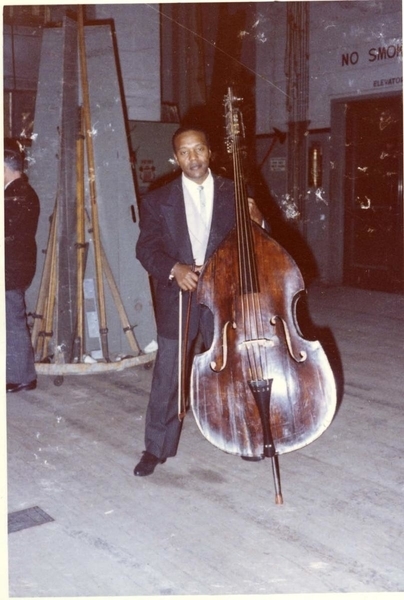

This month the San Francisco Symphony celebrates the remarkable career of bassist Charles Burrell, who became the first African-American member of a major American orchestra when he joined the SFS 60 years ago. In this excerpt from Larry Rothe’s San Francisco Symphony history Music for a City, Music for a World, we trace Burrell’s journey from playing jazz in the neighborhoods of Detroit to fulfilling his dream of performing with Pierre Monteux as a member of the San Francisco Symphony.

Even before Charles Burrell joined the San Francisco Symphony in 1959, African-American musicians had been members of symphony orchestras in the United States, but none had yet found a post in so prominent an ensemble.

Burrell was born in Toledo, Ohio, in 1920 and grew up in Detroit. He started lessons on the string bass and tuba when he was twelve, and not long after that he tuned in his crystal radio set to a San Francisco Symphony broadcast. It was most likely a Standard Hour performance. He remembered the conductor. Pierre Monteux. “That was the exact moment I determined that I wanted to become a professional musician,” he said years later. His goal became more specific. He wanted to become the first black musician in the San Francisco Symphony.

He graduated from what was then a top music school, Cass-Technical High School in Detroit. Cass-Tech alumni were usually prime candidates for orchestra work. Charlie Burrell was not. He was black.

His first teacher, the Detroit Symphony’s principal bass player, agreed to take him as a student, but only on condition he not play the classics. The classics were for white people. Charles Burrell was glad for the instruction and ignored the condition. Later, when he began studies with another Detroit Symphony musician, Oscar Legassey, he discovered he had been taught incorrect techniques, on purpose. Legassey was different. He encouraged him. He set standards. He demanded that Burrell study the classics. But, as most bass players know, music is about more than the classics of the concert hall. Burrell also played jazz. He was sixteen when he began lessons with the great Milt Hinton. “He gave me my first real lessons in jazz and also my first real lesson in life. I mean he taught me some things you don’t learn in books. I mean how to be a person, how to take care of and respect yourself, and how to respect others.”

Fats Waller, Lionel Hampton, Billie Holiday—Charlie Burrell played with them all. Then he enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music. It was 1941, wartime, and soon he was in the Navy, playing in the first-ever all-black Navy band. Stationed near Chicago, he continued his studies at Northwestern University, then completed his music degree at Wayne State. A teaching job in the Detroit schools was denied him because of his color. No matter. It was as a classical musician that Burrell wanted to make his mark. Milt Hinton told him to keep at it, told him he could do it.

He did. His first orchestra job was with the Denver Symphony. Then, in 1959, he was visiting his cousin in San Francisco. He was parked near the War Memorial Opera House. As he was leaving his car, he noticed the bass case in the back seat of a vehicle just pulling up. He struck up a conversation with the driver, who happened to be Philip Karp, the San Francisco Symphony’s principal bass. Karp asked him if he was interested in auditioning for the orchestra. Fast forward to Burrell’s first rehearsal as a member of the San Francisco Symphony. He was at his place in the section when the conductor walked on stage. A guest conductor. Many years later, Burrell recalled that day. “If there were one moment in my life as a musician that I consider my glory, it was showing up for that first rehearsal with the San Francisco Symphony when out walks Pierre Monteux. It was like the Messiah had walked in. There has never been a moment like that before or after. That was paradise. That was the greatest musical moment in my life.”

Charles Burrell remained with the orchestra for five years. He left for the reason many non-natives leave. Enrico Caruso had forsaken San Francisco after the ground had shaken him awake in April 1906. Burrell felt the earth heave and concluded he needed no more of that. He returned to the Denver Symphony, where he performed until 1999. “Music is my great love affair and, in fact, it is my first [love] and always has been my first.” Besides, he had accomplished what he set out to do when he was 12.—Larry Rothe

Larry Rothe, former editor of the San Francisco Symphony’s program book, is author of the SFS history Music for a City, Music for the World and co-author of For the Love of Music. Both books are available at the Symphony Store in Davies Symphony Hall.

[Based on “Charlie Burrell: A Denver Musical Legend,” by Andrew Hudson and Purnell Steen]

Charles Burrell Now

Since his retirement Charles Burrell has lived in Denver where he recently celebrated his ninety-eighth birthday. In a recent interview Mr. Burrell reflected on his time with the SFS:

“When they accepted me into the orchestra as the first non-white member, that was a big thing. I had struggled for almost twenty-five years to make it happen. I was overwhelmed with the fact that they had accepted me and treated me with such dire respect. That was the thrill of my life at the time.

“Music is a unifying force and a force for people to be better people period. That was my whole ambition. To make it much better for people to get along together.”